Charles Darwin famously said in 1859, “It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent… It is the one that is the most adaptable to change.” But Darwin’s perspective is no longer just about animal species; it’s also about current models and data.

165 years after Darwin published his theory of evolution, we find ourselves not in the Galapagos Islands, but rather the ethereal realm of AI models and methods. My first encounter with Charles Darwin in AI was my introduction to the Pareto Front, as part of my research in building an LLM for advanced manufacturing. It’s what’s known as a multi-objective optimization, and it belongs to a bucket of “evolutionary AI methods” that are, in fact, inspired by Darwinism.

The Pareto Front is when you have a collection of solutions where improving one objective worsens another objective. In terms of a business, an example of the Pareto Front would be a software company trading off the efficiency of reading from a database versus writing to a database. In any case, the trade-off of key objectives will always influence a company’s decisions, strategy, and ultimately, success.

After some thought, I began to wonder whether the Pareto Front could be refactored into a Corporate Darwinian Function, such that even a CFO or CEO could predict the survivability of his or her organization. As this thought is somewhat similar to Einstein’s General Relativity, and well beyond my intelligence, it seemed obvious to reach out to Arjun Srinivasan Kudinoor, a current PhD Student in Physics at MIT, who is also part of Protegrity’s Quantum team, to comment and clarify. He presented the following:

In a competitive market, each business can be viewed as a point in a multi-dimensional performance space, Y = { y1, … , yn }, where each yi is a business objective (or metric) like cost efficiency, product quality, customer satisfaction, innovation, etc. These metrics are affected by the set of all decisions X = { x1, … , xm } taken by the business, such as pricing strategy, supply chain, R&D investment, etc. Formally, each yi is a function of x1, … , xm. The Pareto Front is the set of all objective points (y1, … , yn) in Y such that an improvement in some objective yi worsens at least one other objective.

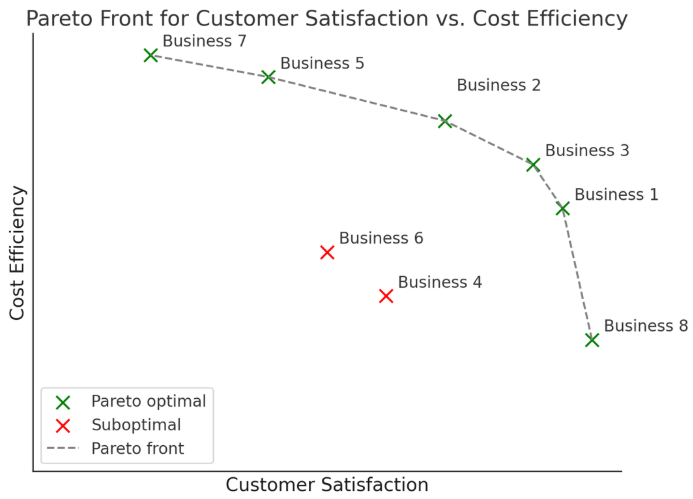

Below is a plot of a Corporate Darwinian Pareto Front in the space of two objectives: cost efficiency and customer satisfaction, where any business beaten by another in both these objectives is outcompeted and lies off the Pareto front.

Arjun continued to explain that in this multi-dimensional landscape of business objectives, a business achieves “Pareto optimality” if no other business performs strictly better in all objectives. There are many functions (linear, logarithmic, exponential, etc.) that one can use to model the probability 𝑃 of a business surviving as a function of its distance 𝑠s away from the Pareto Front. However, all such functions are required to obey a universal condition:

dP ds < 0, when the distance away from the Pareto Front s > 0.

This formalizes the intuitive idea: the further a business lags on all key metrics, the lower the probability of its survival. To ensure survival, a business must be on (or push toward) the Pareto Front of business performance in its industry.

So, how does a business ensure Pareto optimality? One way is to excel in a unique objective that others are not addressing. For instance, in many businesses, data is owned by different organizations, with different temperaments on sharing. Some of the hesitancy comes from regulations, compliance, some comes from privacy and confidentiality, and some comes from power. Regardless of the reasons, this approach must be obliterated, especially knowing that every business today must compete or market with the hyperscalers of the world, and they are “eating up” your data.

To survive, businesses must create and own “first-class” data that isn’t just proprietary but also maximally shareable across all their teams and systems. It also has to be data that the hyperscalers don’t have. That means don’t just encrypt or tokenize data for compliance reasons, do it because you don’t want them to have it. Using superficial masking, or storage encryption, is simply not good enough in this Darwinian era. Creating and owning first-class data that the hyperscalers don’t have is how one can create its own corner of the Pareto Front where no one else can dominate.

Arjun later pointed out that the term “first-class” data suggests some data, and its management, are better than others. Highly specialized, siloed data might perform exceptionally in one system but be unusable elsewhere. In contrast, more shareable data might not be maximally efficient for one use case but is valuable across multiple systems. The Pareto Front of data utility would consist of data solutions that are optimal trade-offs between the utility of data in different contexts. On this Front, you cannot improve data’s usefulness in one system without reducing its usefulness in another – any further global improvement requires a compromise. Information ecosystems that do not lie on the Pareto Front of data utility will be, by definition, inefficient.

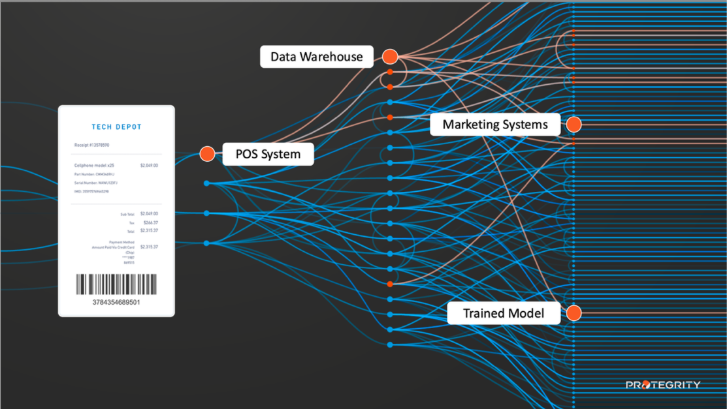

So, when a customer purchases something, like a phone, the federated fan out of the information on that purchase can be wide, deep, continuous, and evolving, crossed over and mutated; how often it’s used, analyzed, compounded, concatenated, and dissected is anyone’s guess. There is no endpoint. That’s why it’s so important for the future of information not to be hard-coded to any one system. It must be shareable across systems and allowed to affect AI models themselves. Such data finds a Pareto optimal balance across many systems only when it is shared and adapted to be used by those systems. That data will not evolve and support other uses if it can’t circulate.

The future of data isn’t unpredictable because natural selection has already given us a bit of a spoiler alert of its future. One of my favorite books, “Thinking Fast and Slow” by the recently deceased Daniel Kahneman, gives this advice:

“The idea that the future is unpredictable is undermined every day by the ease with which the past is explained.”

Michael Howard

Arjun Srinivasan Kudinoor